A Struggle for Funding

-

By Maddy Weber

Originally published in Forward, Winter 2012How one man saved a research institute

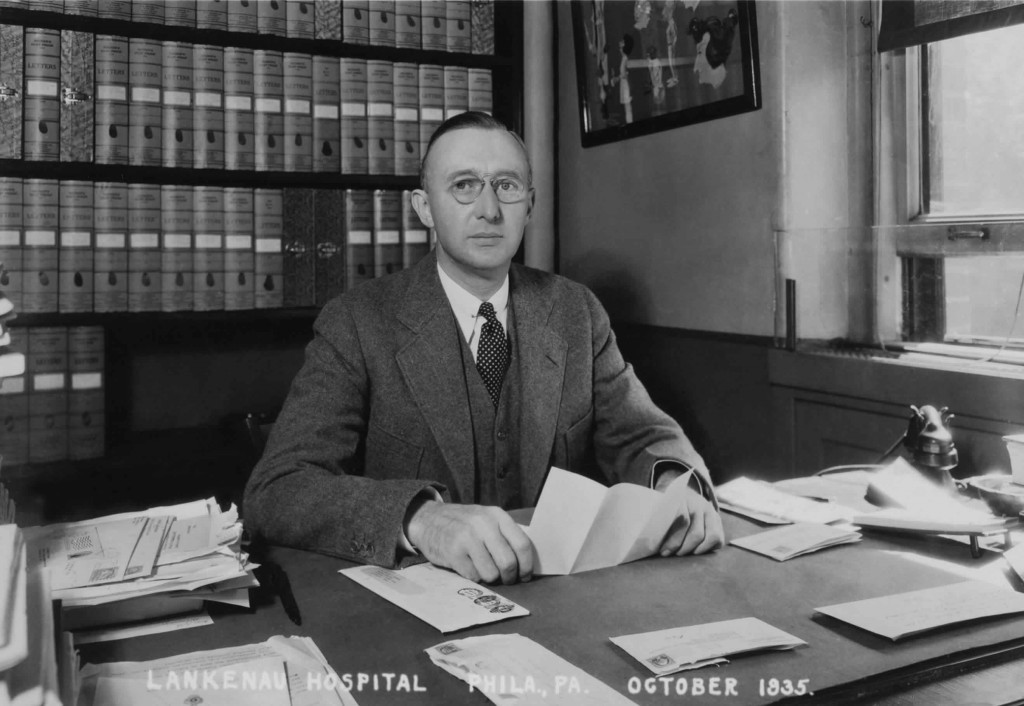

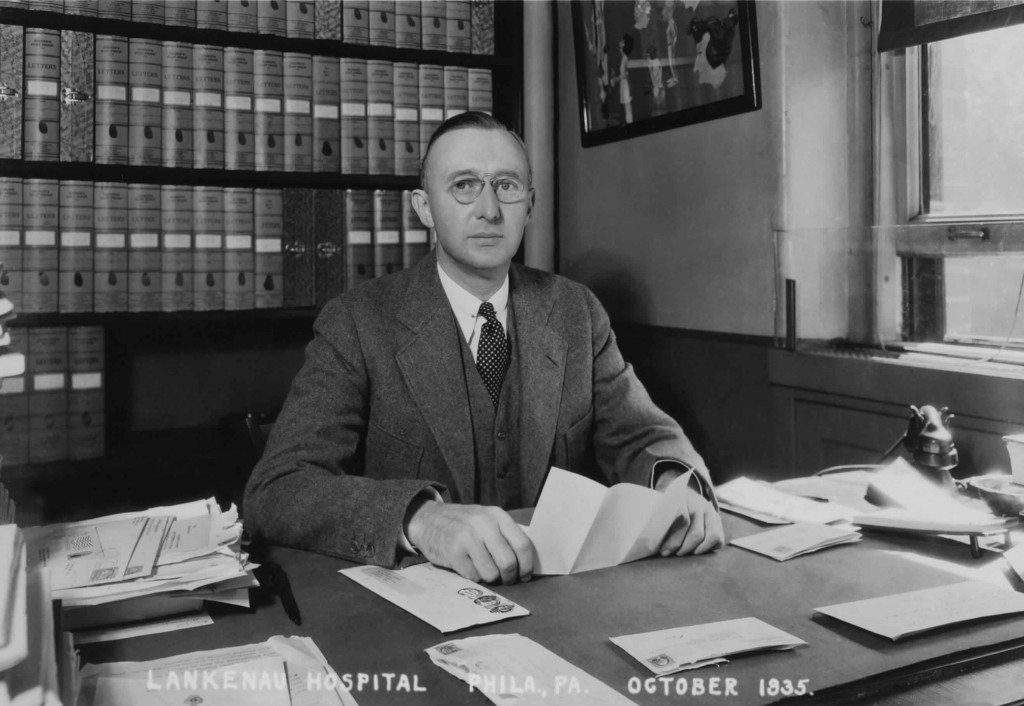

“I spend a good bit of my time trying to wheedle, coax and threaten some of the funds of plutocrats into our coffers.” Stanley Reimann, 1935 Stanley Reimann was just one man, but in September 1930 he faced the daunting task of sustaining a fledgling research institute dedicated to unraveling the causes of cancer.

As the country descended into the grip of the Great Depression, the Lankenau Hospital Research Institute—later to become the research enterprise of Fox Chase Cancer Center—was coming into trouble of its own. Funds from the estate of benefactor Rodman Wanamaker, who had died in 1928, had run dry, and fundraising efforts by Reimann, the institute’s founding director, had so far met with frustration.

“I spend a good bit of my time trying to wheedle, coax and threaten some of the funds of plutocrats into our coffers for research,” he wrote to one colleague. The letter is one of hundreds Reimann sent—many now yellowed with age—that are archived in Fox Chase’s Talbot Research Library.

A pathologist, Reimann was convinced that exploring normal cell growth would shed light on tumor development. It was a novel, even unpopular idea at the time, but with Reimann as its advocate, the institution had quickly gained esteem in the international scientific community since its founding in 1927. Now, however, the hospital’s trustees— not scientists themselves—doubted the enterprise, given its shaky finances. They gave Reimann an ultimatum: prove the institute’s worth or it would have to close.

No stranger to a challenge, Reimann got to work. Per the board’s request to “obtain an independent opinion of the highest order” as to the institute’s merit, he invited authorities in cancer research from across North America to visit Philadelphia. After touring the institute’s stately ivy-covered building, each provided a glowing report attesting to the significance of the research and the abilities of Reimann and his staff. “Surgery, radium and X-rays are of no service in a considerable portion of the cases of cancer,” wrote professor A.B. Macallum of Montreal’s McGill University, referring to the protocols of the day. “Can we conscientiously refuse to explore for other methods of treatment?”

Reimann’s efforts paid off. The trustees voted unanimously to keep the institute open and even came forward with personal contributions, including a $10,000 gift from businessman Irénée du Pont. But even du Pont’s gift made up only a third of the annual budget. Reimann forged ahead, writing letters by the dozens seeking support from bankers, philanthropists, and other people of wealth and influence throughout the region. His correspondence reflected his near-desperation. “We have a building and equipment costing a half million dollars. The building is half empty,” reads one letter from 1931. “Any funds which we obtain can be put directly into salaries and expendable supplies.”

Reimann at the piano, 1956 His efforts to fill the institute’s coffers didn’t end at the typewriter. He plied his hand at another set of keys as well: A skilled pianist, he raised more than $5,000 by playing a series of recitals.

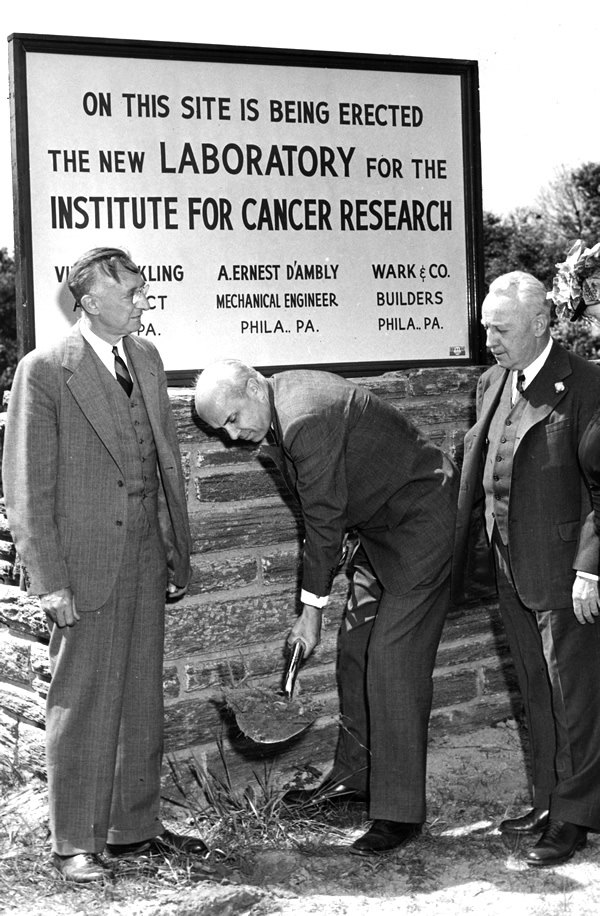

Groundbreaking on the Institute for Cancer Research, 1947. Stanley Reimann (left). Philip T. Sharples, a trustee of Jeanes Hospital and the first president of the institute, holds the first shovelful of dirt. The ICR became the research arm of Fox Chase. Reimann’s dogged efforts, combined with the board’s support, added up. By late 1931, the institute had procured enough funding to cover its day-to-day operations. Change was on the horizon when it came to the institute’s financial stability: The next few years would see the formation of the organization’s first women’s auxiliary, a powerful force for fundraising and public outreach, and within a decade the National Institutes of Health would be established, ushering in an era of federal grant funding for science.

But for a critical period, one man’s determination kept alive a commitment to cancer research—and to the institution that would help form the future of Fox Chase.