David Hungerford and the Philadelphia Chromosome

-

Susan Tobin

Originally published in Forward, Spring 2009Discovery revolutionized cancer research, treatment

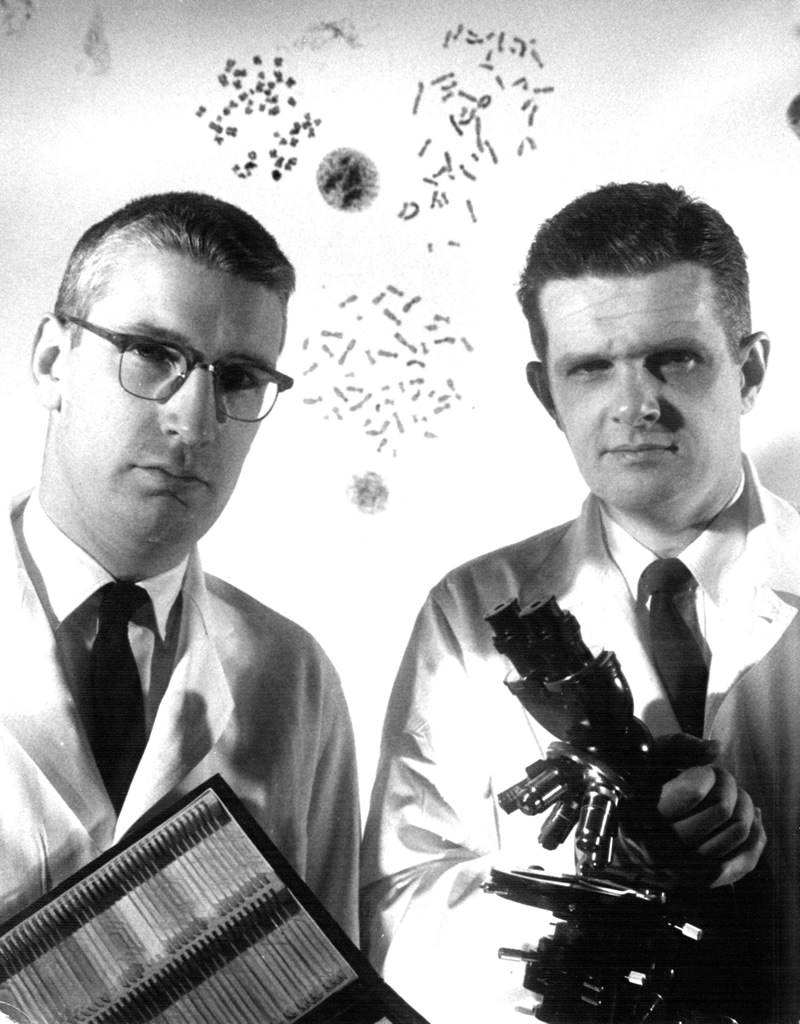

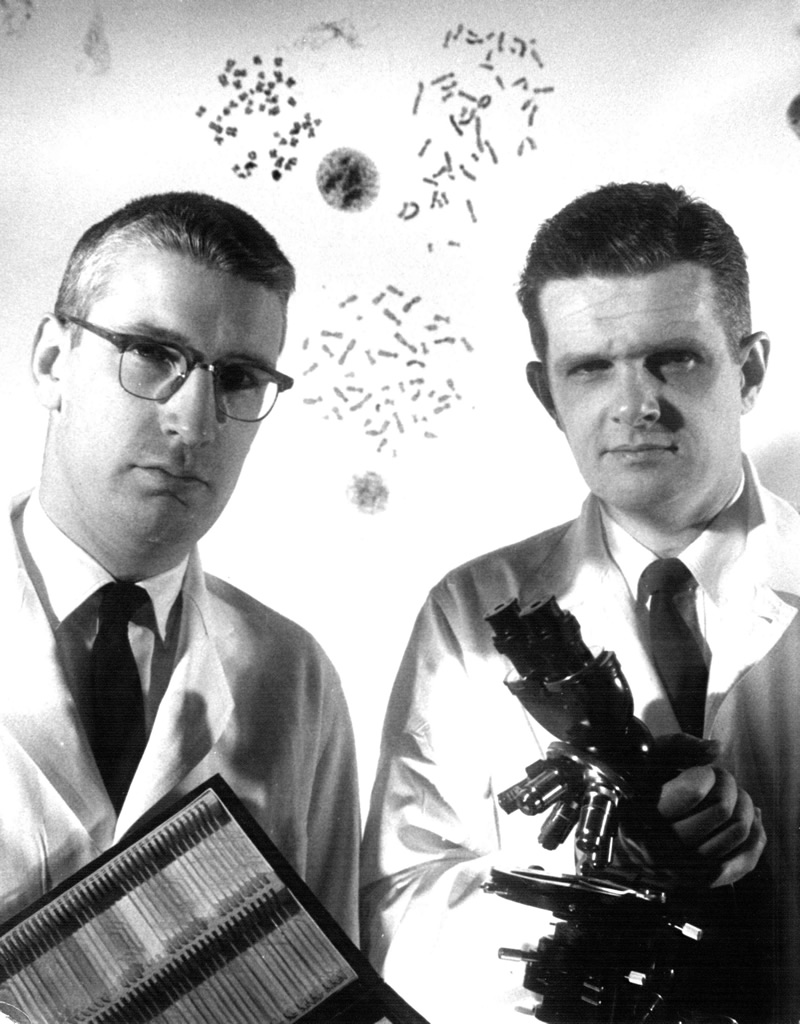

Peter C. Nowell (left) and David A. Hungerford, 1961 Fifty years ago, a landmark discovery at Fox Chase changed the direction of cancer research and paved the way for a new approach to cancer treatment.

The finding came to light when the keen eye of predoctoral fellow David A. Hungerford detected a tiny flaw in chromosomes from the blood cells of patients with a type of leukemia. It was the first genetic defect linked with a specific human cancer.

In 1959, tools did not yet exist to analyze individual genes. Scientists had only crude techniques for studying chromosomes, the 23 pairs of rod-shaped packages of genes at the heart of every blood and tissue cell.

Peter C. Nowell, a pathologist at the University of Pennsylvania, was studying leukemia cells under the microscope when he noticed cells in the act of dividing. To his surprise, their chromosomes—usually an indistinct tangle—were visible as separate structures.

Knowing little a bout chromosomes, Nowell asked around for someone to work with him. He found Hungerford, who worked in a Fox Chase genetics lab and was writing his doctoral thesis on chromosomes. While conducting his microscopic studies, Hungerford made the seminal observation that certain leukemia cells had an abnormally short chromosome 22. The mutation became known as the Philadelphia chromosome.

Later research found that the defect stems from a DNA swap between chromosomes 9 and 22. While 22 transfers material to 9, thus growing shorter, it also gains a normally inactive growth-promoting gene. That gene fuses with a gene on 22 to become a cancer-causing gene, speeding up cell division and blocking DNA repair.

Arising from this genetic mix-up is chronic myelogenous leukemia, a slowly progressing blood cancer that occurs primarily in adults. Ninety-five percent of CML patients have the Philadelphia chromosome.

Gains for researchers and patients

Fox Chase researcher David A. Hungerford prepares a camera to photograph specimens under the microscope. Hungerford discovered the Philadelphia chromosome in 1959. The discovery provided the first evidence that cancer starts with changes in one or more genes. It galvanized the field of molecular biology—the study of such vital molecules as DNA, RNA, and the proteins that do each cell’s work.

The Philadelphia chromosome became an important tool for diagnosing CML and monitoring treatment. More importantly, the linking of culprit genes with cancers led to the creation of targeted drugs that block the effects of cancer-causing mutations. Because these therapies zero in on cancer cells sparing normal cells, they cause fewer side effects.

The first such drug, Herceptin, targets the gene involved in an aggressive form of breast cancer. Gleevec, another targeted therapy, blocks the effects of the cancercausing gene on the Philadelphia chromosome and has proved effective in treating CML, as well as a rare sarcoma called gastrointestinal stromal tumor, or GIST.

Today, scientists continue to develop innovative new cancer treatments that provide better outcomes for patients, building on a discovery made five decades ago by a young Fox Chase researcher.

Originally published in Forward, Spring 2009

Ed. Note: David Hungerford died November 3, 1993, at the age of 66. Peter Nowell died December 26, 2016, age 88.