A pioneering leader in cancer immunotherapy, Louis M. Weiner, MD, Director of Georgetown University’s Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center, delivered the 2025 Robert L. Krigel Endowed Memorial Lecture at Fox Chase Cancer Center. Held on December 12 in the Leidy Auditorium, the lecture held both personal and professional meaning, honoring a life-changing relationship and the life’s work of both its namesake and its presenter.

Established in 1995, the lectureship honors the life and legacy of Robert L. Krigel, MD, a Fox Chase oncologist whose early and influential work in biologic and translational cancer therapies helped shape modern immunotherapy. Krigel died in 1994 but left an enduring mark on Fox Chase and his colleagues.

Weiner previously delivered the memorial lecture in 1996 before returning this year. The audience included former colleagues, along with Bonnie Perlmutter, PhD, Krigel’s spouse.

From left: Louis Weiner, Director of Georgetown University’s Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center; Martin Edelman, Professor and Chair, Department of Hematology/Oncology, Fox Chase Cancer Center; Bonnie Perlmutter, Dr. Krigel’s spouse; Hossein Borghaei, Professor, Department of Hematology/Oncology at Fox Chase

“It is hard nowadays to find mentors like Lou has been, somebody who goes really beyond just being someone to tell you what to do,” said Hossein Borghaei, DO, MS, Professor in the Department of Hematology/Oncology at Fox Chase, and a former member of the Weiner lab. “We all have mentors in various stages of our careers, but nobody has had an impact on my career as Lou did because he looked beyond the fact that I didn’t go to an Ivy League school and he understood what was within me.”

As a former member of the Weiner laboratory, Borghaei described Weiner as the consummate mentor, clinician, and leader. “He is a true scientist, in that there is nothing that he doesn’t find interesting or feel curious about,” Borghaei said.

Of Friendship and Compassion

Weiner began his talk remembering his friendship with Krigel and his entire family, a relationship that endures. “Rob was my best friend,” Weiner said. “There was no second place at that point.”

The two began at Fox Chase on the same day in 1984 and worked closely together until 1993, when Dr. Krigel left to become the founding director of the Lankenau Cancer Institute. By the time Krigel joined Fox Chase as Director of Hematology, he had already developed a reputation at New York University as a leading authority on Kaposi’s sarcoma in the context of the emerging HIV epidemic. At Fox Chase, Krigel conducted pioneering clinical research on the use of combination cytokine immunotherapies in cancer.

During those years, Weiner and Krigel collaborated scientifically while also building lives side by side, living close to each other in Elkins Park. “Our wives became friends, we raised our families, went to soccer games and baseball games, vacationed together,” Weiner recalled. “He was my wingman. I was his.”

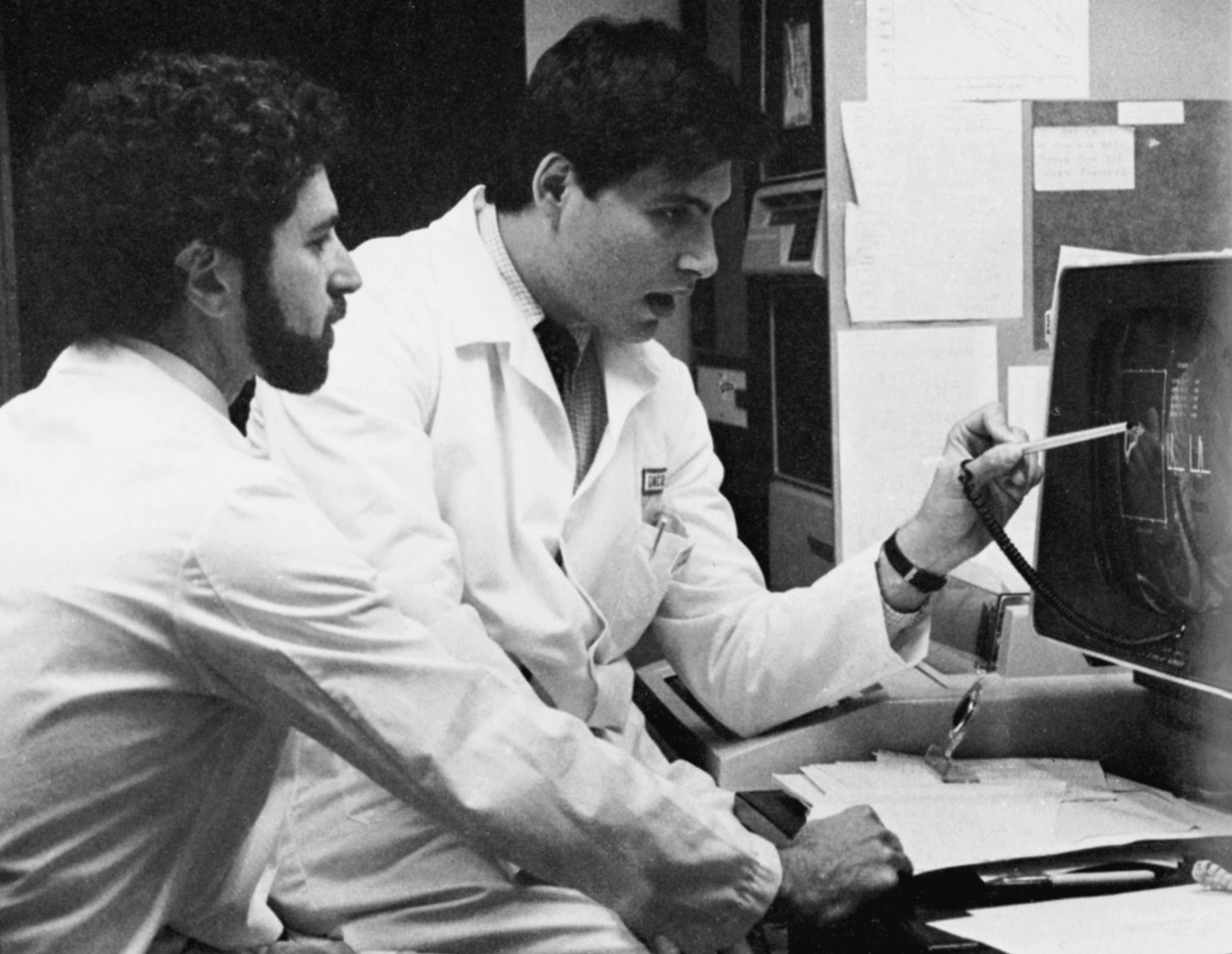

Robert Krigel MD (left), and Louis Weiner, MD, at Fox Chase Cancer Center, 1986

“I still think of Rob as a wonderful man, father, and friend. He coached Little League and soccer, and was active in the community,” recalled Perlmutter in a separate conversation. “I received letters from his patients long after he died. He wasn’t just a good clinician – Rob listened; he was caring and kind.”

Their families remain deeply connected to this day, which Perlmutter describes as a lasting blessing over three generations. “Our oldest boys met 40 years ago and remain best friends, our grandkids are friends,” Weiner noted.

Weiner recounted in detail the day in 1993 when Krigel called him from home, thinking that he had perforated an ulcer. Weiner took him to the ER at Jeanes, where Krigel was admitted. “I just happened to be the attending physician on service that day,” Weiner said. “So, my best friend was on my service.”

Imaging revealed a devastating diagnosis—metastatic angiosarcoma involving the liver and spleen.

“I had to go look at those films and then I had to tell Bonnie and Rob,” Weiner explained. “Rob insisted on looking at the slides.”

Weiner described Krigel paddling into the Radiology reading room, staff members in tears after he entered. They all knew, he said, and they all loved him.

“He was a very good doctor. He knew what was coming.” Krigel then asked something that would change Weiner forever: “Lou, I want you to be my doctor.”

Krigel lived for six more months with widely metastatic disease. Weiner described Krigel’s last public appearance at Weiner’s son’s Bar Mitzvah, where Krigel danced in a wig. “It was heartbreaking and it was wonderful,” Weiner said.

After Krigel’s death, Weiner delivered the eulogy in the same auditorium where he now stood. “It was without question the hardest thing I’ve ever done in my life,” he said, “and the most wonderful.”

“Until that moment, I didn’t understand what it meant to care for someone—to have that intense emotional attachment and feel their pain,” Weiner said. “And even though we lost Rob, he lives on through me because I think of him every time I see a patient.”

“I am eternally grateful to him for what he did for me,” Weiner said.

Following Krigel’s death, Bonnie Perlmutter gave Weiner a carved wooden Buddha, made by one of Krigel’s patients who had died of AIDS. It stayed on Weiner’s desk at Fox Chase and he took it along with him to Georgetown, describing it as a tangible reminder of Krigel’s compassion and humanity.

In 2013, when Anna Krigel graduated from medical school at NYU, where her father had been on faculty, Weiner sent her the Buddha as a gift, noting how his friend’s spirit now lives through her in this way.

Turning Up the Heat in a Cold Pancreatic Tumor Microenvironment

Weiner then turned to the scientific focus of his lecture: immunotherapy for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), a disease he described bluntly as “bad.” Pancreatic cancer is projected to become the second leading cause of cancer-related death by 2030 and has a five-year survival rate of approximately 13%, as opposed to 70% for all cancers combined.

Central to Weiner’s research is the pancreatic tumor microenvironment—the matrix of cells and tissue surrounding and sustaining the cancer cells. In particular, the dense fibrous barrier that surrounds pancreatic tumors. This fibrotic tissue—rich in collagen, laminin, and fibronectin and driven by cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs)—creates a powerful barrier to immune cells. “You look at a pancreatic cancer slide, and all you see is fibrous tissue,” he said.

Weiner describes it as a “cold” tumor microenvironment, because there are few active immune cells nearby. Meanwhile, the area is awash in immunosuppressive molecular signals.

Pancreatic cancer responds to very little and is a good model of resistance to everything, says Weiner, and much of the scientific discussion has been focused on what makes these cells tick. According to Weiner, however, the discussion may be ignoring the physical reality, and he remained curious about the fibrous tissue, “There’s got to be a reason why it’s there.”

Weiner’s lab first sought to demonstrate that this fibrous barrier was, in fact, actively preventing immune cells from attacking pancreatic tumors. “It’s almost like a Maginot Line,” he said, “protecting the epithelial cells from immune attack.”

They demonstrated that, as the amount of fibroblast increases, the microenvironment becomes denser, which prevents immune cells from infiltrating the matrix of fibrous material to get at the tumor. His team showed that myofibroblast CAFs are the dominant source of signaling within the PDAC tumor microenvironment, effectively “conducting” what Weiner described as a “malignant orchestral piece.”

To overcome this barrier, his lab pursued a second strategy: stimulate the intrinsic ability of immune cells—especially natural killer (NK) cells—to punch through the fibrous wall of the tumor microenvironment. This led to a focus on fibroblast activation protein (FAP), an enzyme that features predominantly on the surface of CAFs.

FAP is often overexpressed – or over-produced by the protein-making machinery within cells – in both autoimmune disease, like arthritis, and cancer. In fact, decades ago, members of Weiner’s lab had looked at FAP as a cancer target at Fox Chase. At the time, he conducted an early-stage clinical trial with BXCL701, a drug that attacks multiple targets including FAP, to little benefit.

More recently, however, a current MD/PhD student in Weiner’s lab at Georgetown had become convinced that NK cells also produced FAP in abundance. It was an idea that is counterintuitive – especially since FAP is overexpressed in tumor cells – and met with skepticism, yet a forthcoming paper in the journal Immunology from the Weiner lab provides evidence to the case.

By overexpressing FAP in NK cells, Weiner’s team showed that these cells could seek out CAFs and “eat their way through the tumor matrix,” in cell models of the tumor microenvironment. In mouse models, tumors treated with FAP-overexpressing NK cells showed significant anti-tumor effects. The experiments strengthened the importance of helping immune cells breach this defensive barrier around pancreatic tumors.

“When we finally saw pictures of sheets of NK cells inside the tumor,” Weiner said, “I thought, I’ve been waiting for this image for 30 years.”

According to Weiner, this led to a strategy of combining multiple means to coerce immune cells to munch their way through the protective fibrous barrier and find their cancer targets. Indeed, Weiner notes, solid tumors might resist the emerging generation of CAR-T therapies because these activated immune cells cannot fight their way through the tumor microenvironment and attack cancer cells.

Their findings brought Weiner back to the aforementioned BXCL701, also known as talabostat. It inhibits FAP and a number of other enzymes, which collectively has an anti-fibrotic effect. The idea was to see if BXCL701 could work synergistically with a drug that would stimulate immune cells – a one-two punch that would cut through the defensive fibrous barrier around pancreatic tumors while activating cancer-killing immune cells to attack.

The combination, they reasoned, could turn a cold tumor microenvironment into a hot zone of immune cell activity.

One such approach combined BXCL701 with pembrolizumab (also known as Keytruda), which is a drug that inhibits a molecule that cancer cells often use to trick immune cells into ignoring them. In animal models, the combination produced long-term survivors and a profound remodeling of the tumor microenvironment.

These findings translated into a multi-center Phase II clinical trial, led with Georgetown collaborator Ben Weinberg, MD, earlier this year, which tested BXCL701 plus pembrolizumab therapy in patients with metastatic PDAC. Nearly half of the patients experienced some clinical benefit. Responding tumors showed dramatic increases in immune cell infiltration.

“It’s not a home run,” Weiner said, “but it’s a bunt single and, in pancreatic cancer, we’ll take that.”

The lab is now exploring combinations with other immunotherapies to reduce resistance and extend the duration of response by breaking through the tumor microenvironment.

Compassionate Care and a Sense of Fox Chase

Following the talk, Borghaei presented Weiner with a recreation of The Diamond, a miniature version of the sculpture that sits in front of the main clinical entrance at Fox Chase Cancer Center. The Diamond represents how multiple aspects of Fox Chase come together to support patients—a fitting, emphatic point to cap Weiner’s lecture.

Weiner’s talk was a powerful reflection on the relationships that strengthen Fox Chase, both professional and personal. The lecture also served to remind us of Robert Krigel’s lasting influence on the field and on the people who knew him, and to highlight Fox Chase’s role as a place of personal meaning and purpose as well as healing and research.

Weiner closed with words that captured both gratitude and legacy:

“I grew up here. Fox Chase Cancer Center taught me how to think. Fox Chase taught me how to lead,” he said. “Rob Krigel taught me how to care—and how to be a better doctor and a better man.”