Is Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy the Best Tool to Diagnose Melanoma?

-

The diagnosis of melanoma can be a very scary and anxiety provoking time. As a medical oncologist who specializes in treating patients with melanoma, most of my patients have had a biopsy performed by their primary medical doctor or dermatologist before they see me. They are typically referred to me for a treatment recommendation and further management.

Based on my experience, I want to stress the importance of seeing a melanoma specialist at the initial time of diagnosis to review your biopsy in order to develop a definitive expeditious plan of treatment.

One procedure specifically related to melanoma is the sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB). This tool is used to properly stage the melanoma, which in turn, may help physicians develop the most effective course of treatment. Not all patients who have melanoma require, or are candidates for, this minimally invasive procedure. However, there are pathologic nuances and discussions that should take place between you and your physician to assist you in making an educated and informed decision about this procedure.

SLNB is recommended for all patients with melanoma tumors of intermediate thickness (between one and four milimeters in depth): Studies have shown that the technique is useful for identifying small areas of melanoma cells that have spread to the lymph nodes, which account for about one-third of all melanoma cases. SLNB detects cancer in the sentinel node in about 18 to 26 percent of these patients.

Performing SLNB for thin melanomas (less than 1 mm) is more controversial. Thin melanomas are the most common form of melanoma, and can usually be cured through surgical excision alone. This excision can be done either using local anesthetic in the office, or with sedation in the operating room. There is evidence to suggest that a melanoma that is greater than 0.76mm in depth may have an increased risk of spreading to the lymph nodes. While SNLB is not necessary in many cases, the guidelines suggest that melanomas with certain high-risk factors seen under the microscope, such as an ulcerated tumor or rapidly dividing cancer cells (mitoses), may warrant SLNB.

Thick melanomas are uncommon, but have a higher risk of spreading to lymph nodes or elsewhere in the body. My practice is to recommend SLNB in this population as it provides additional information for staging the disease.

Every patient seen at the Fox Chase Cancer Center Cutaneous Oncology Program has his or her biopsy slides reviewed by our dermatopathologist as a second opinion.

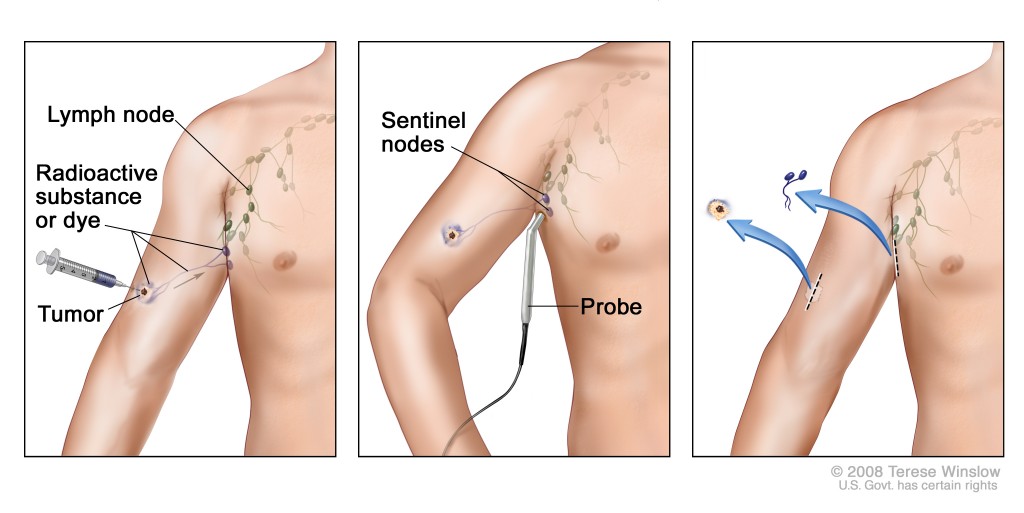

Overall, the SLNB procedure itself in experienced hands has very low risk. At Fox Chase on the morning of surgery, my patients undergo a test called lymphoscintigraphy with technetium (a low level radioactive dye). This test evaluates and maps out which lymph nodes have the highest chance of harboring melanoma. This test does not show if the melanoma spreads but helps the surgeon to identify which lymph nodes to remove. At that point, we use general anesthesia to help the patients rest during the procedure.

Before the surgery begins, we inject a blue dye called lymphazurin around the melanoma. This dye also spreads through the lymphatic channels and collects in the sentinel lymph node. The procedure itself takes approximately 30 to 40 minutes and is accomplished through a two to three centimeter incision at the same time the primary site of the melanoma is removed. Generally between one and four lymph nodes are removed during this procedure and are sent for special studies and staining in the pathology lab. The results of this usually take seven to 10 days.

As with any procedure, there are risks, that I discuss with my patients. These include post-operative fluid collection, which generally resolve on their own; temporary irritation of the nerves; infection; and a very low incidence of chronic lymphedema or swelling of the arm or leg (depending on where the lymph nodes are removed). The chance of lymphedema occurring is relatively low - around a five to seven percent chance.

As an oncologist, I like to explain the nuances of cancer with my patients. I believe melanoma specialists should have an educated discussion with their patients regarding the risks and benefits of a procedure and arrive at a mutually agreeable plan. This is certainly true for SLNB for melanoma.